Ever since Yogi Adityanath became chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, there have been allegations of ‘Thakur-raj’, or dominance by upper-caste Thakurs, in the state. His ascent to power added ballast to the older idea that the BJP was an upper-caste dominated party and that its political rise from 2014 onwards was driven by these communities. Recent political science research on India has claimed a significant resurgence of upper caste dominance between 2009-2019 within the BJP. Most recently, the Paris-based Sciences Po’s Christophe Jaffrelot declared that the 2019 poll marked ‘the revenge of the upper-caste elite,’ aligned with the ‘BJP against the Dalits’ and OBCs’ assertiveness’.

Jaffrelot and Ashoka University’s Gilles Vernier have argued that ‘the last decade has seen the return of the savarn (upper caste) … and the erosion of OBC representation … along with the rise of the BJP.’ In Parliament, overall, they claimed that BJP dominance was driven by 36.3 per cent upper-caste MPs within the party and only 18.8 per cent OBCs (the lowest OBC representation in a major party, compared to the Congress and the regional parties) in a recent academic caste profile of the 2019 Lok Sabha. Do such claims hold up to facts on the ground?

New caste data that we have put together, however, shows that research and scholarship on the party have lagged behind the party’s reality. In June 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi pointed out in a video address to his party workers that BJP was represented by 113 OBC, 43 ST (Scheduled Tribe) and 53 SC (Scheduled Caste) Members of Parliament in the Lok Sabha. In other words, a full 37.2% of BJP Lok Sabha MPs were OBC, 14.1% ST and 17.4% SC. This meant that a whopping 68.9% (209) of all its 303 Lok Sabha MPs elected in 2019 were non-upper castes and from castes that were traditionally considered lower down in the caste hierarchy. This is strikingly on par with the widely accepted national share of the population of these castes: 69.2%. The charge of upper caste domination is difficult to make with such electoral representation. If you leave out seats reserved by law for SCs and STs alone, non-upper castes still accounted for almost 60 per cent of BJP elected from general constituencies. Within this, as many as 50 per cent (113) were OBC.

It is impossible to square these two claims: Modi on the one hand and Jaffrelot (who used a database on the social backgrounds of elected legislators co-produced by Ashoka University’s Trivedi Centre for Political Data) on the other. There can’t be grey areas on facts, though there can be differing interpretations of what they mean.

To critically reassess the emerging picture, we put together the Mehta-Singh Social Index which studied the caste backgrounds of thousands of Uttar Pradesh politicians between 1991-2019. This is because caste in UP is notoriously difficult to pinpoint by only looking at names on a list. Vermas from Noida are Gujjars (OBC), Vermas from eastern Uttar Pradesh are Scheduled Castes, Vermas from near Bulandshahar are sunars (OBC), Vermas from the Awadh region are Kurmis (OBC) and those from eastern UP are Kayasths. Similarly, Chaudharys from Ballia are Yadavs, those from western UP are Jats, while those from four UP districts are Kurmis. Kushwahas can be both upper caste Rajput or OBC. Rawats from Uttarakhand are Rajputs/Thakurs while Rawats from UP are Pasi Dalits (SCs). Likewise, Chandras can be SC or Thakur/Rajput. Tyagis are Brahmins in western UP but some Tyagis in eastern UP are Scheduled Caste. Some Tyagis from Meerut are also Bhumihars. No wonder, sometimes even local residents get the castes of people in nearby regions wrong.

Overall, we studied the castes of:

• 2,560 Lok Sabha candidates fielded by the BJP, SP, Congress and BSP in each of UP’s 80 Lok Sabha constituencies and in every single national election over three decades (1991-2019).

• 1,612 Vidhan Sabha candidates fielded by the four parties in 403 assembly constituencies in the state in the 2017 state election;

• 42 state-level BJP office-bearers in UP in 2020;

• 101 government ministers in UP, stretching across BJP chief minister Yogi Adityanath’s council of ministers (54) in 2020 and SP chief minister Akhilesh Yadav’s council of ministers (47) in 2012.

• 98 district-level BJP presidents in UP in 2020.

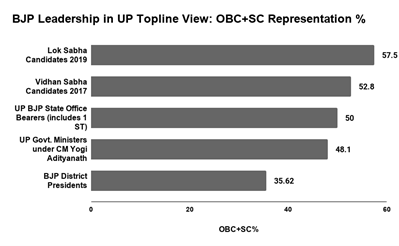

The findings of the Mehta-Singh Social Index shed new light on the BJP’s social engineering experiments with caste in UP. To give a bird’s-eye view of the numbers, OBCs and SCs accounted for:

• 57.5% of the BJP’s UP Lok Sabha candidates in the 2019 general election

• 52.8% of its candidates in the 2017 assembly poll that it swept

• 50% of its office-bearers in the state in 2020

• 48.1% of Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath’s council of ministers

• 35.6% of the BJP’s district-level presidents

Table 1: BJP OBC and SC Representation in BJP Leadership in Uttar Pradesh: Topline view

Source: Fieldwork and analysis by Mehta-Singh Social Index. Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha candidates analysed from ECI data. Figures for Vidhan Sabha 2017 include figures for some seats contested by BJP alliance partners. UP BJP office-bearers analysed from party list issued on 23 August 2020. UP BJP government ministers list is accurate as of 30 October 2020. UP BJP district presidents’ list is based on party listing as of 25 July 2020.

These numbers revealed by the Mehta-Singh Index showcase why it is misleading to characterise the new BJP under Modi and Shah as a party dominated by upper castes. It is quite the reverse. The BJP, between 2013 and 2019, saw a remaking of not only its social support base but also of its internal organisational systems with OBCs being given centre stage. In a state where OBCs are 54.5% and Scheduled Castes 20.7% of the population, the BJP was ahead of all major political parties in proportionally representing candidates from these castes in the Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha polls and inching closer towards it in other political structures.

The BJP in UP, after 2013, put up significantly more OBCs as candidates than its political rivals: SP, BSP and Congress. It also gave them more space in its internal power structures in the state, radically shifting its organisational DNA. So much so that OBCs and SCs, taken together, came to occupy half or more than half of the leadership positions at virtually every level of the party, barring its district presidents.

To be sure, upper castes, which number about 24.2% in UP, are still over-represented and remain integral to the party, but the proportion is much less than before. The great increase in representation of OBCs and SCs in the BJP’s structures changed the perception of the party on the ground, in relation to its explicitly caste-based political opponents: SP (with OBCs) and BSP (with Dalits). The direction of change in the BJP and how it started sharing power with castes that had been relatively ignored by national parties is unmistakeable. Caste remains a central lever of power in Indian politics, and the BJP’s social engineering has been a key part of its growth.

All of these political structures needed re-examining because looking at one piece of the caste puzzle is not enough and can sometimes be misleading. The point of creating the Mehta-Singh Social Index and doing this 360-degree caste sweep of UP politics was to get a holistic picture of how representative or unrepresentative the BJP has been of castes, how this changed over time and how it compared with rival political formations.

Sharing the Spoils of Power: The BJP’s New OBC Tilt

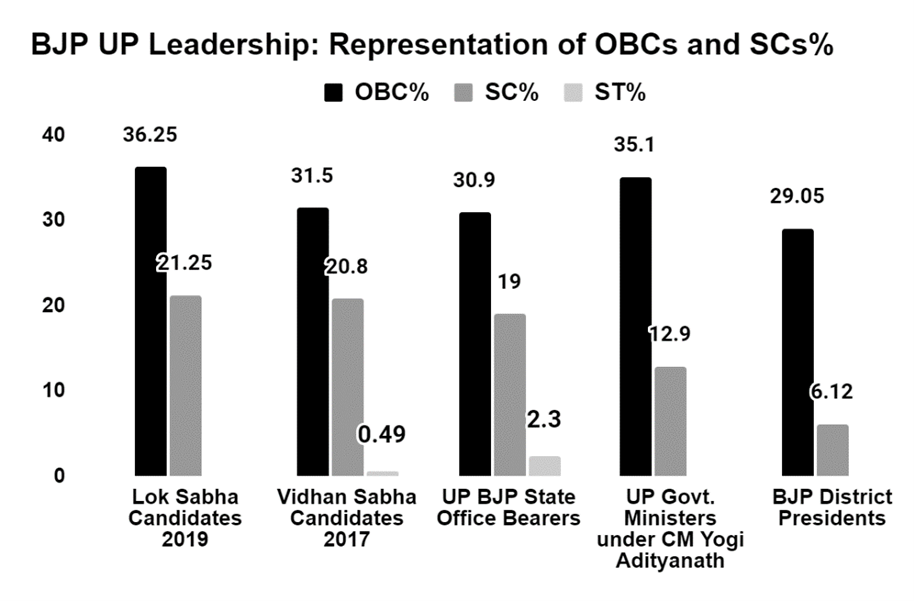

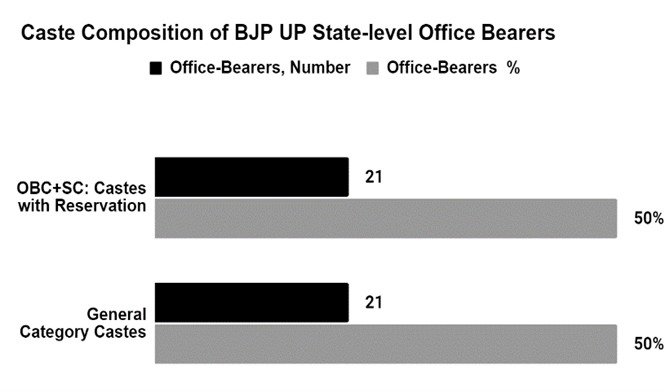

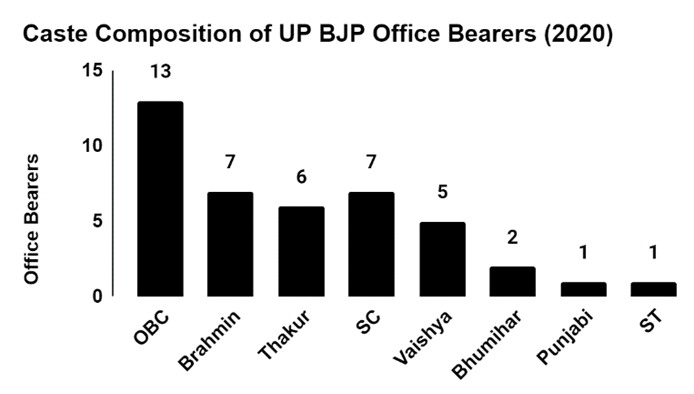

By 2020, OBCs accounted for over 30 per cent of the BJP’s top office bearers in the state and SCs over 16 per cent. Of the party’s apex state leadership—consisting of its president and almost four dozen vice presidents, general secretaries and secretaries—thirteen were OBCs, the highest of any caste, followed by ten Brahmins and seven Thakurs. By 2020, OBCs and SCs together accounted for 46.5 per cent of the BJP’s top brass in UP.

Figure 2: Caste Composition of UP BJP Office-Bearers, 2020

Source: Fieldwork and analysis by the Mehta–Singh Social Index. UP BJP office-bearers analysed from revised party list issued on 23 August 2020. Data includes president, vice presidents, general secretaries, secretaries and two morcha presidents (Mahila Morcha and Yuva Morcha) since these are not caste-specific categories. Other morcha leaders have been excluded from this list because these are caste-specific posts.

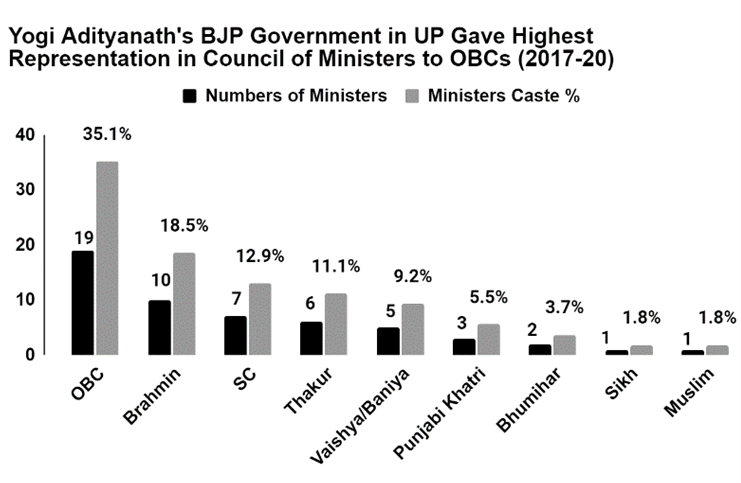

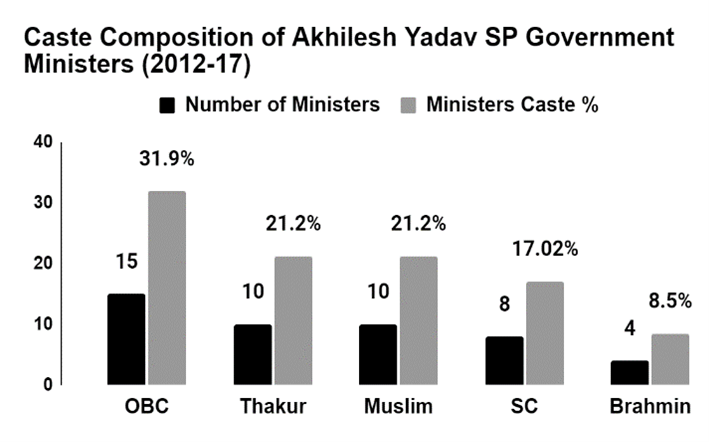

It is not a coincidence that we see exactly the same caste break-up in Yogi Adityanath’s council of ministers. While one of the dominant media narratives around his government has been of a renewed Thakur dominance, the fact is that OBCs again constituted the single highest caste category in his council. Nineteen (35.1 per cent) of fifty-four ministers in the BJP state government in 2020 were OBCs. This was thrice the number of Thakurs (six, 11.1 per cent) and almost twice the number of Brahmins (ten, 18.5 per cent).

Figure 3: Ministers in Yogi Adityanath’s Government More Representative Across Castes Than Ministers Appointed by Akhilesh Yadav’s Preceding Government

Source: Fieldwork and analysis by Mehta–Singh Social Index. Based on Yogi Adityanath’s Council of Ministers list, accurate as of 30 October 2020. Akhilesh Yadav’s Council of Ministers as per list issued by UP government in 2012.

The nature of the BJP’s shift becomes clearer when we compare it to what came before. It had almost exactly the same percentage of OBC+SC ministers (48.1 per cent compared to 48.9 per cent) as Akhilesh Yadav’s preceding SP government did. This is a striking number when you consider that the BJP has always been seen as a party of upper castes, while the caste-based SP purports to be a party of social justice, and explicitly so in OBC terms. Significantly, Yogi Adityanath’s government has more OBC ministers than Yadav’s (see Figure 3). The big difference is that, while most of Akhilesh Yadav’s fifteen OBC ministers were Yadavs, only one of BJP’s nineteen OBC ministers happened to be a Yadav—a clear reflection of the new social coalition of non-Yadav OBCs and non-Jatav Dalits that the BJP had forged in UP (see Figure 3).

The changed representation of these castes in the BJP’s political structures—its election candidates, ministers and office bearers—was part of a planned political outreach.

BJP No More an Upper Caste-Dominated Party: Why Scholars Got it Wrong

The BJP’s strategies underscored how powerful caste identities remain the truest indices of social power in India. While caste dynamics keep changing, political representation matters immensely. The BJP’s leaders understood this, and the changes they made to their organisation in terms of caste representation at every organisational level played a vital role in its electoral triumphs.

This new evidence shows how our understanding of the BJP’s caste representation has so far not kept pace with ground realities. The revelations of the Mehta–Singh Index should lead to much-needed soul-searching as well as a correction of methodologies and dominant narratives among academic experts who study caste patterns in political representation. These findings put a very serious question mark not only on their academic research—which ignored observations from a whole host of journalists on the ground in UP, all pointing strongly to a contrary trend—but also on the poor oversight mechanism of the university research centres that churned out the wrong data and the peer-reviewed academic journals that published them.

There is need for both introspection and more transparency. We can have differing interpretations of facts, of course, but only if the data itself is correct. When institutions that are the touchstones of academic credibility produce misleading data, it skews our basic understanding of society and erodes public trust. We hope the findings of the Mehta–Singh Index will start a much-needed debate.

This is first of a three-part series by the author in the run-up to Assembly elections.

Dr Nalin Mehta is Dean, School of Modern Media, UPES; Advisor, Global University Systems; Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University Singapore.