One of the most revealing sidelights of this election has been watching the intellectual twists and turns of a battery of ‘experts’ — academics and journalists — who predicted an SP landslide for days. Then, when the exit polls came out, many of these experts, without batting an eyelid, switched to explaining the exact opposite trend, with detailed arguments to boot. As if they had been seeing it all along. Many journalists, for example, travelled to UP. Some came back predicting an SP wave. ‘Aandhee chal rahee hai’, a few tweeted. Crowds can often provide a misleading picture in an election, especially if one doesn’t carefully account for their social composition. The Samajwadi Party (SP) did not manage to significantly expand beyond its core base of Yadavs and Muslims in this election, drawing an automatic glass ceiling on its growth.

Among the funniest tales on the election grapevine this season was that of a veteran journalist who after Phase 1 and 2 of counting confidently predicted 42 seats for Jayant Chaudhary’s RLD alone in western UP. Until it was gently pointed out that the party had fielded only 33 candidates.

As Samir Saran, President of Observer Research Foundation, tweeted, many of these experts got it so dead-wrong because they ‘persisted with outdated assumptions and their personal biases’.

You got it right @nalinmehta – others … persisted with outdated assumptions and their personal biases #UPElections https://t.co/9meHbzZG9a

— Samir Saran (@samirsaran) March 10, 2022

There was another particularly special category of expert political scientists too. When faced with the exit polls data, Gilles Verniers, Assistant Professor at Ashoka University who heads its Trivedi Centre for Political Data, actually argued on television on March 9 that ‘there is no very clear history [sic] of a positive co-relation between performance in governance and electoral performance’ in India. He was responding to NDTV’s Sreenivasan Jain, on Reality Check, who argued that he was seeing ‘a new phase in India’ where ‘governance has been delinked from voting preferences’, and the ‘largely you don’t see that discontent translating into electoral choices’.

In other words, in this view, the people were voting against their interests, probably didn’t know what’s good for them — they should have listened to the analysts who thought they knew better — and were being swayed by other considerations.

This narrative reminded me a little of the Columbia University professor Edward Said’s seminal argument in his Orientalism about how the West constructed the idea of the ‘Orient’ as the childish, somehow less-intelligent ‘Other’, in opposition to its own self-image of superiority and rationality. In this case, the election ‘experts’ seemed to be ‘Othering’ the voters.

Indeed, an entire gamut of panelists repeated how they were ‘perplexed’ that the ‘boisterous’ Akhilesh campaign ‘that they had all been affected by’ was not translating into votes. This theme of election outcomes being delinked from ‘governance performance’ was then repeated ad nauseum on results day. The less said about this propensity to blame voters in a democracy for their choices the better — but it is a strange argument that not only disrespects voter intelligence but the idea of democracy itself.

It would have been funny if it wasn’t so insulting and patronising to voters. It also had more than a vestige of what Rudyard Kipling had called the ‘White Man’s Burden’ — the idea that elites had to somehow uplift the masses who really were too unintelligent to know what was good for them.

Why did so many experts, who really should have known better, get these elections so wrong. Here are three reasons why:

1. BJP EXPANDED ITS SOCIAL BASE. MANY EXPERTS REFUSED TO BELIEVE IT

The BJP’s UP triumphs in 2014, 2017 and 2019 had been powered by its forging together a new social coalition cutting across castes (retaining upper caste support but gaining new voters who were largely non-Yadav OBCs and to a lesser extent non-Jatav Dalits). This social shift was documented by the data in my recent book, ‘The New BJP’. Far from reversing, the 2022 result reflected a further strengthening of this social coalition of the BJP in UP and a deepening of its roots (see for instance, CSDS post-poll survey and the India Today-Axis My India exit poll numbers on caste).

Leading into the election, however, many experts simply refused to acknowledge the past shifts on the ground. They insisted that the ‘new BJP’ post-2014 remained as upper-caste dominated as the ‘old’ BJP was. When some of the BJP’s OBC ministers defected to the SP during the campaign, many got convinced that what they saw as the BJP’s ‘Potemkin’ village on social composition was breaking down. Many didn’t realise that the BJP’s penetration into OBC groups was much deeper and that most of the leaders who defected didn’t have a mass base of their own. Indeed, some of them like Swami Prasad Maurya eventually lost their own seats.

The deep-rooted resistance to accept empirical realities was the outcome of a narrative which insisted on basing analysis more on political pamphleteering than on any sound academic methodology. For instance, the Paris-based Sciences Po’s Christophe Jaffrelot declared in 2021 that the 2019 poll marked ‘the revenge of the upper-caste elite,’ aligned with the ‘BJP against the Dalits’ and OBCs’ assertiveness’. Jaffrelot and Ashoka University’s Gilles Vernier argued that ‘the last decade has seen the return of the savarn (upper caste) … and the erosion of OBC representation … along with the rise of the BJP.’

In Parliament, overall, Vernier and Jaffrelot wrongly claimed that the BJP dominance was driven by 36.3 per cent upper-caste MPs within the party and only 18.8 per cent OBCs. In actual fact, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi pointed out in 2020, a whopping 68.9 per cent (209) of all 303 BJP Lok Sabha MPs elected in 2019 were non-upper castes (113 OBC, 43 ST and 53 SC ).

The Mehta-Singh Social Index, that I put together with journalist Sanjeev Singh for ‘The New BJP’, showed that research and scholarship on the BJP have long lagged behind the party’s reality. To give a bird’s-eye view of the numbers in UP, OBCs and SCs accounted for:

• 57.5 per cent of the BJP’s UP Lok Sabha candidates in the 2019 general election

• 52.8 per cent of its candidates in the 2017 assembly poll that it swept

• 50 per cent of its office-bearers in the state in 2020

• 48.1 per cent of Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath’s council of ministers

• 35.6 per cent of the BJP’s district-level presidents

When these findings were published, these ‘experts’ instead of engaging in a debate on facts, unfortunately resorted to shooting the messenger — in a public debate that unfolded on News 18’s pages here.

Meanwhile, the old rules of Indian politics had shifted. By 2022, OBCs became by far the single most represented caste category in the BJP at every organisational level. As I have argued earlier, the BJP post-2014 became by far the most representative of all castes in UP (barring Muslims) compared to its rivals. In the process, upper-caste dominance in the party was significantly reduced. The deepening of that trend powered its victory in 2022.

2. DIRECT-BENEFIT-TRANSFER PROGRAMMES WORKED. EXPERTS REFUSED TO SEE IT

A key reason behind the BJP’s stunning victory that broke so many previous patterns of UP politics was that it recreated itself as a ‘party of the poor’. When Yogi Adityanath took charge as chief minister in 2017, he made effective execution of all Union schemes his top priority. Modi called this ‘double-engine ki sarkar’ in his campaign publicity.

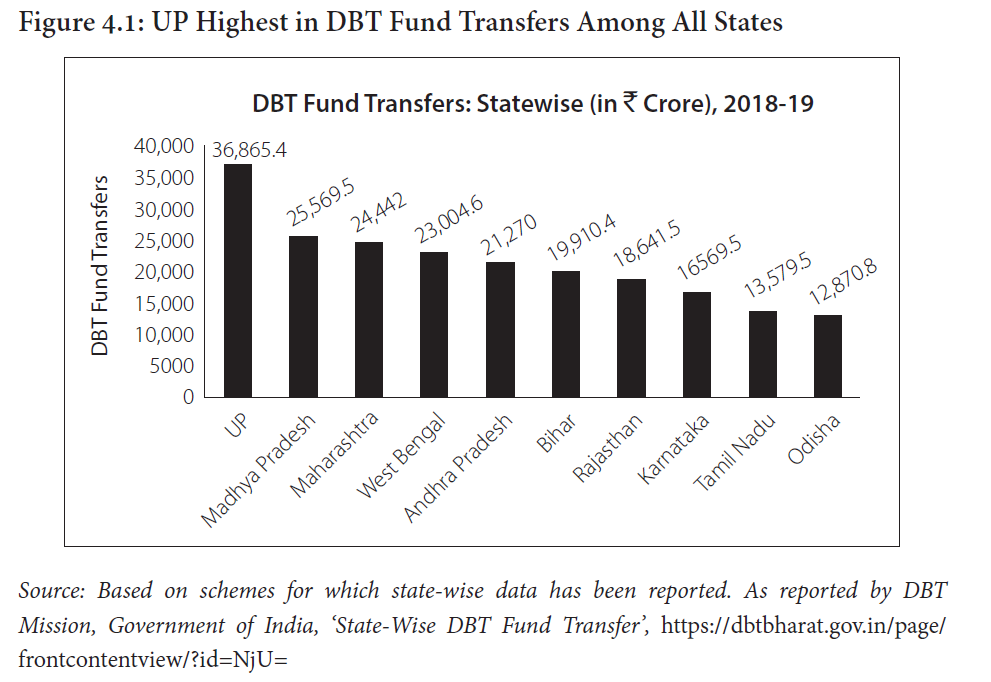

Many experts simply dismissed government programmes either as overhyped or simply as rhetoric. In practice, however, a focus on delivery of government schemes and political mobilisation around it drove the BJP’s advances. UP, for example, reported the highest number of total DBT fund transfers among all states in 2018-19. Partly, this is by virtue of it being India’s most populous state. Even so, it was ahead by a wide margin on DBT in a state-by-state comparison of the highest-spending states (Figure 4.1).

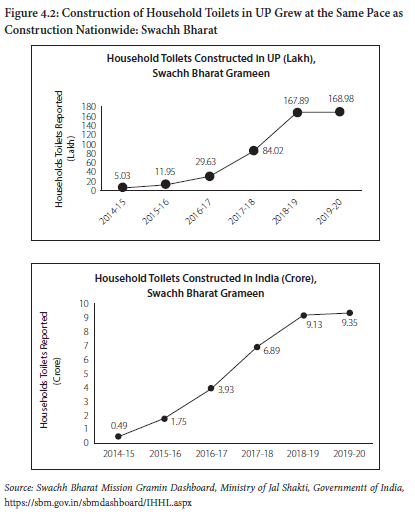

The pace of construction of household toilets under Swachh Bharat and housing under Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana-Gramin illustrate the Yogi government’s focus on implementing Union government schemes. UP constructed 17.1 million household toilets between 2014-15 and 2019-20, taking the overall tally to 23.8 million in UP and 164.18 million nationally (see Figure 4.2). Revealingly, Modi began referring to these toilets as ‘Izzat Ghar’ or ‘House of Respect’ after seeing this title-plate on some toilets built in Varanasi in 2017. In a country where a lack of toilets has been one of the most obvious yet underrated gender divides, this terminology for toilets specifically targeted women.

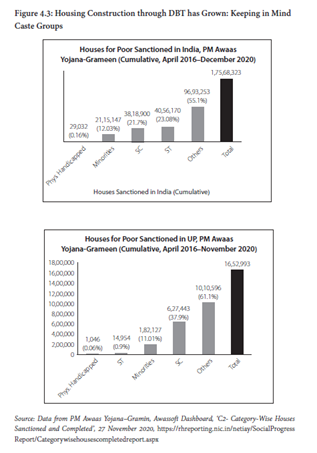

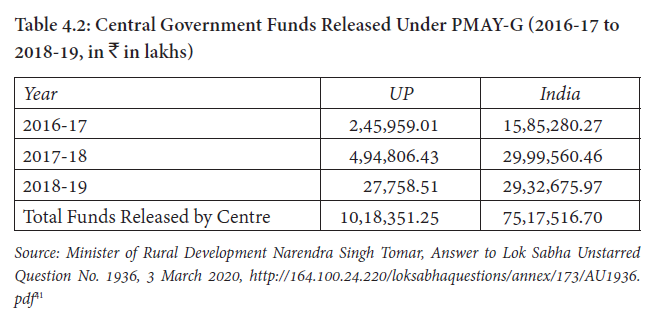

The PMAY-G was formally launched on November 20, 2016. By November 2020, a whopping 17.5 million houses had been sanctioned under this scheme for the poor. Over 12 million of these approved houses had already been constructed and over 1.6 million (1.4 million completed) were in UP. Just as with household toilets, these houses are not constructed by the state but funded by it. Beneficiaries (those who lived in kaccha/dilapidated houses) received DBT of Rs 1,20,000 to build their own houses and were also entitled to receiving 90 days of unskilled labour under MGNREGS in a scheme that was funded in a 60:40 ratio by the Union and state governments.

Importantly, governmental policies ensured a good balance of minority groups and disadvantaged castes among the beneficiaries. Government data shows that 23.08 per cent of houses were sanctioned for STs, 21.7 per cent for SCs and 12.03 per cent for religious minorities during this period nationwide. In UP, over one-third of houses went to SCs and 11 per cent to minorities (see Figure 4.3).

The BJP did not just focus on DBT schemes; it added an extra layer of political mobilisation using grassroots booth-level organisation structures. Crucially, most of the outreach to labharthees happened outside of election cycles. In effect, the party sangathan became the foundation for a new kind of system. This mobilisation around welfare was new. ‘We always had a sangathan,’ says Dinesh Sharma, deputy chief minister. ‘Now we added some new points to it.’

BJP leaders are right to argue that they are not winning on Hindutva alone. As one official told me, ‘Many others came before with Hindutva. There was Swami Chinmayanand and others earlier. What happened to them? If it was only Hindutva, Yogi Adityanath would also have got wiped out.’ This is why, they told us, Hindutva is the ‘gati’, it was welfare that was the wheel.

3. THE WOMEN FACTOR, WHICH MANY EXPERTS SUDDENLY SEEMED TO DISCOVER POST-RESULTS

The making of a new women vote has powered the BJP since 2014. This was based on a clear communications outreach to women voters fronted by PM Modi, greater representation than before for women in leadership positions within the party hierarchy and a whole host of schemes, as documented in ‘The New BJP’. For example, women accounted for 68 per cent of PM Mudra Yojana loans, 66.9 per cent of houses built under PM Awas Yojana-Gramin (women alone or jointly with their husbands), 56.84 per cent of Atal Pension Yojana beneficiaries, 53.3 per cent of Jan Dhan and 81 per cent of Stand Up India.

In 2022, the BJP’s growing support base among women widened further. The CSDS post-poll survey for UP, for example, showed that the BJP’s lead over the SP among women was 13 per cent in UP. The India Today-Axis My India data, which polled 32,000 women, showed this gap to be 16 per cent in favour of the BJP among women.

Yet, we have the spectacle of scholars like Neelanjan Sircar, at the Centre for policy Research (CPR), now raising questions on the exit-poll and post-poll data itself — including on Jats. CPR’s Rahul Varma was writing as late as March 2 that ‘Ultimately, the road to Lucknow does not look that easy for either side. Many ground reports suggest that SP has a significant edge over the BJP in the first two phases.’ In the event, the BJP easily won these last first two phases.

Since the result, Sircar has even tweeted a warning on exit poll caste data, saying, ‘WARNING: Don’t over-interpret survey data on castes & jatis. The exit/post poll data aren’t constructed for this purpose (samples aren’t randomized at this level) Also I haven’t seen any uncertainty calculations on estimates (a function of both sample size & sample uncertainty)’. He then added, ‘For those wondering, there are a lot of statistical solutions to this problem. Here’s one: Run a Bayesian hierarchical model & report appropriate credible intervals (and the model).’

For those wondering, there are a lot of statistical solutions to this problem.

Here’s one: Run a Bayesian hierarchical model & report appropriate credible intervals (and the model) https://t.co/4Zl2CC68Tw

— Neelanjan Sircar (@NeelanjanSircar) March 13, 2022

To cut through the ho-hum, the simple question is: if all this data is wrong, what explains the massive BJP victory? Was it just upper castes, then? If everyone else is wrong, do you have alternative data of your own? When I asked a major pollster who conducted one of the exit polls about this seeming denial of reality, he responded simply by saying, ‘Let them continue to live in that [denial of reality].’

Finally, predicting elections is not an exact science. Anyone can make an honest mistake to get a poll trend wrong, of course. The real problem is when so-called experts persist with outdated analytical frameworks despite evidence to the contrary, when they confuse their own preference for what they would like to see happen with analysis and plain old bias.

Elections in India need to be understood on the ground — not from the ivory towers of elite theorising to fit pre-fixed narratives. And just deploying highfalutin English words or faux American accents is not a substitute for genuine ground understanding.

This is third of a three-part series by the author on the Assembly elections. You can read the first part here and the second part here

Dr Nalin Mehta is Dean, School of Modern Media, UPES; Advisor, Global University Systems; Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University Singapore. He is the author of The New BJP: Modi and the Making of the World’s Largest Political Party, Westland Non-Fiction: 2022. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.