As Indian athletes get ready to compete in Incheon today few remember how the modern Asian Games themselves were virtually invented by India, how central these Games were for the hopes, aspirations and ideals of Nehruvian India and the role they played in soft power diplomacy in the early years after independence.

“You have certainly made India the capital of Asia,” wrote Anthony de Mello to Nehru after the success of the first Asiad in Delhi in 1951. De Mello organised the inaugural Asiad, apart from founding BCCI, and the birth of this pan-Asian sporting festival in Delhi symbolised a fascinating interplay between the role of sport and the rise of Indian nationalism and its hopes of leading a new postcolonial order in Asia.

As nationalist elites from Beijing to Tokyo began to see success in western sports as essential to their quest to become more `modern`, creating such sporting events became a necessary adjunct to political struggles with colonial powers. The Far Eastern Asian Games (1913-1934) and the Western Asiatic Games (1934), sponsored by Patiala`s Maharaja in Delhi, emerged from this aspiration as early Asian prototypes of de Coubertin`s Olympics. Both these imitative attempts ended because of World War II and the difficulty of defining Asia itself: did it extend from the Suez to Singapore or all the way to Suva in Fiji?

At a deeper level though, the idea of Asian unity was an article of faith with Indian nationalists and drove the creation of Asiad. Figures like Keshab Chandra Sen and Swami Vivekananda were important proponents of Asianism and Tagore famously saw Asia as a continent of “eternal light”. By the 1920s Gandhi, C R Das, Srinivas Iyengar and M A Ansari mooted an Asian federation and Congress Working Committee even passed a resolution for it in 1928. India was to be its leader.

The idea of the Asian Games itself was born on the eve of independence, at the 1947 Delhi Asian Relations Conference. Nehru personally raised funds for the conference and was clear about his Asian idea: “For too long we of Asia have been petitioners at Western courts… That story must now belong to the past.” With 21 countries attending and similar sentiments by Gandhi and Sarojini Naidu animating the conference G D Sondhi, a Cambridge-educated college principal from Lahore, conceived the idea of an Asian Games Federation.

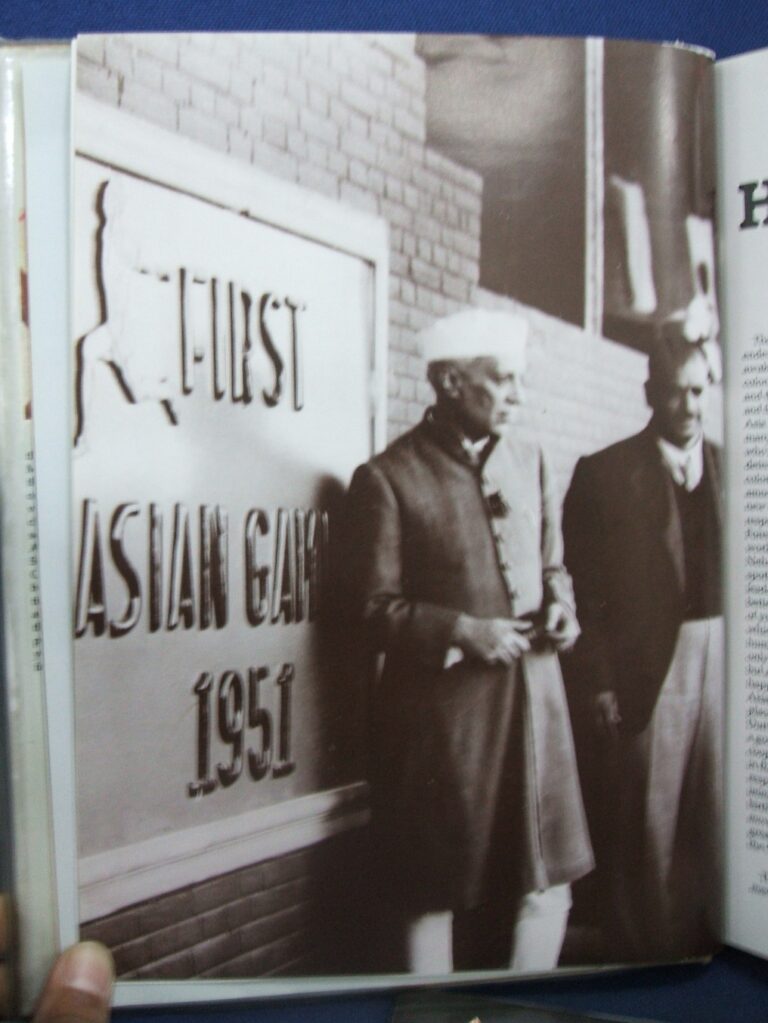

Nehru was supportive, seeing it as a tool for bringing Asian countries together. The Maharaja of Patiala provided funds and Sondhi organised another conclave of Asian sporting administrators in Delhi in 1949 to mid-wife the Games. Nehru himself changed their name from Asiatic Games to Asian Games and coined their motto: “Play the Games in the Spirit of the Games.”

It was one thing for Nehru to support the Games, another to pay for them. With millions of refugees crowding Delhi and the army deployed in Kashmir, the 1951 Delhi Asiad had government patronage but little official funding. The Filipinos spent £100,000 for the second Asiad in Manila, the Japanese built a new stadium in Tokyo for the third but Delhi in 1951 was essentially organised by a volunteer group which included army chief General Cariappa, who lent army facilities, personal contributions from Patiala, Kapurthala and those of Anthony De Mello who borrowed Rs 1 lakh from his cricket club. This was the essence of Nehruvian India: hope, new aspirations and a spirit that had still not been extinguished by disappointments to come later.

When 600 contestants from 11 countries finally marched into the new National Stadium on 4 March 1951, chief organiser de Mello was moved enough by the symbolism to write to Nehru that “no event outside the field of sport has done more to further Asian unity” and that New Delhi was now the “new capital of Asia”.

Just a year earlier, Nehru had been disillusioned enough by political squabbles with Asian leaders to dismiss all unity attempts as “useless”. The Delhi Games renewed his faith and the 1951 Asiad is a forgotten missing link in the story of Nehruvian diplomacy that eventually led to the Bandung conference.

The Asian Games today, however, are a far cry from those idealistic beginnings. Currently they are a full-fledged sporting extravaganza second only to the Olympics. There`s little doubt that the standard of competition in Asian Games is far better than Commonwealth Games or Pan-Am and at times even the European Championships. With China, Japan and Korea represented in full strength, the Asian Games bring out the best in athletes and are the pre-eminent platform to test oneself a year and a half before the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio.

The one fact that connects the modern Games with their beginnings is the soft power argument. All host nations use the Games for their soft-power projection on the world stage, in a mini version of what states do with the biggest sporting spectacle of all, the Olympics. India too is a part of this process. Real success at Incheon for example can finally transform India into a multi-sporting nation. With reasonable success at London 2012 and Glasgow 2014, the stage is indeed ripe for a sporting revolution of sorts. Success at the Asian Games will not only advance this process significantly, it will also breed a sports culture — which India has been craving since Nehru declared the first Asian Games open in Delhi in 1951.